By Vincent Foucher

For decades, policymakers have been calling to save Lake Chad. More recently, they have insisted the shrinking of the Lake was both the cause and consequence of Boko Haram. This narrative is not fully corroborated by scientific research and comes with risks.

In 2018, the United Nations Environment Programme released a media piece titled “The tale of a disappearing lake”. The account was indeed a compelling one: over the last 60 years, it said, Lake Chad’s size has decreased by 90 per cent as a result of the overuse of water, extended drought and climate change. It also noted that the jihadi insurgency often designated as Boko Haram has only made things worse. The tale has kept reverberating in various ways and it stands at the heart of this Spotlight article.

In November 2022, Bola Tinubu, the candidate of the All Progressives Congress (APC), Nigeria’s ruling party, for the 2023 presidential election, echoed the notion that Lake Chad was disappearing in a campaign speech [Editor’s note: Nigeria’s electoral commission INEC announced on 1 March 2023 that , Tinubu won the elections in February]. He insisted he would make good on the longstanding Transaqua project: the replenishment of Lake Chad by diverting part of the waters of the Congo Basin via a 2,400 km-long canal.

The Transaqua project, estimated to cost about 50 billion USD, has been around since the 1970s. It was revived in the 2010s, as both a solution to the drying out of the lake and to the Boko Haram insurgency. In 2018, the project became policy for the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), the intergovernmental regional body grouping all states of the Lake Chad Basin. The LCBC has seen its initial economic cooperation agenda extended to the coordination of efforts to curb Boko Haram. The notion that the Boko Haram conflict is related to the climate crisis – whose most spectacular manifestation is the drying up of Lake Chad – is very much entrenched in policy circles. International relations scholars call this “securitisation”: the transformation of an issue into a matter of “security” through a series of discursive manoeuvres, thus giving it new relevance.

Lake Chad is a powerful site from which to reflect on the uneasy meeting between the climate crisis, an undeniable fact on a global level, and the specificities of a major security crisis. The present contribution discusses the questionable accuracy of the narratives of policymakers and their problematic success.

What the Data Say

The data are clear about Lake Chad: currently it is not drying up. As demonstrated by geographer Géraud Magrin, the “myth of the disappearing” Lake is based on a remarkable ellipse: he compares the lake at a high in terms of water level in the 1960s with its current situation, pointing out that the decades in between have been rather disregarded, thus obscuring the fact that the lake was even lower in the 1970s and 1980s and that it has actually been replenishing itself at least since the early 2010s, as confirmed recently by Pham-Duc and his colleagues. Long-term rainfall predictions are a risky exercise, but when it comes to Lake Chad, they tend to show an increase in rainfall rather than a drought. As such, the myth of the disappearing lake depends on a failure to take stock of a data series in full.

Magrin and other geographers who have researched the production systems around the Lake have questioned another key assumption in the take of the policymakers: they have insisted that the indisputable diminution of the surface of the Lake compared to its high point of the 1960s was not necessarily all negative. It has certainly affected fishing and irrigated agriculture negatively, but it has made available to farmers a very fertile soil, allowing for a spectacular expansion of agriculture in the area.

What the Jihadi Say

Since 2018, I have interviewed dozens of former fighters hailing from the two factions of Boko Haram in Nigeria, Niger and Cameroon, of whom only one mentioned climate as a direct factor in his decision to join the insurgents. A young man from the Niger Republic described how, in the early days of Boko Haram’s jihad, a terrible flooding along the banks of the Komadugu River killed much of his cash crop. Having lost everything, he felt that joining Boko Haram for a season or two could be a way to start over. A climatic disaster thus played a fairly direct role in his decision to join jihad. So, more than drying up, the immediate climatic problem in Lake Chad seems to be the increasing variability of the climate: notably, heavier but shorter rains.

The stories most recount about their affiliation to Boko Haram reflect the changing trajectory of the movement itself: a hard core of believers, who wanted to oppose Nigeria’s government which they considered corrupt, hostile and impious; kids taken along by a relative; students in Quranic schools taken away by their Quranic teacher; people forced to join or be killed; young men from poor families promised money, a bike and a wife; others trying to protect their community from the jihadi by joining them; others wrongfully arrested by the security forces and who escaped from prison during a jihadi attack on the prison and who felt their best chance to survive was to follow the jihadi – complex and multifactorial stories, and testimonies that navigate between crushing contradictory forces. The climate crisis is part of that, certainly, but it cannot be considered the main explanator factor for the Boko Haram crisis.

The Transaqua Project: A Solution or Another Problem?

That the replenishment plan would still be defended by many leading policy figures in the face of contradicting evidence is indeed remarkable. This is all the more fantastical as there are good reasons to believe that – beyond being an unwise allocation of resources (for instance, there are better things to do with 50 billion USD in the Lake Chad Basin) – rather than a solution, the Transaqua project could be another cause of conflict.

The flooding of fertile land would be a short-term catastrophe for the farmers – they would have to relocate to less fertile land elsewhere, hoping that the new irrigation afforded by the replenished lake could compensate for that loss. And the project comes with many other problems. The building of the canals to redirect part of the Congo River Basin would result in mass land expropriations in areas of great political fragility, where states have a limited capacity to administer conflict and can resort to unadulterated violence when attempting to do so. Poor governance – a key factor in the Boko Haram conflict itself – would also be a problem in a multi-billion dollar project spanning across a huge area, affecting the livelihoods of millions. Of note, Chad, Cameroon and Nigeria have some of the worst governance ratings in the world. In sum, a 50-billion-dollar project could help turn the lame Leviathans that govern the Lake Chad Basin into more corrupt, larger, clumsier and unwieldier structures.

The Appeal of a Simple Tale?

All this begs the question: why has the narrative of the shrinking lake been so attractive to policymakers, despite evidence that it is inaccurate and potentially harmful? Drawing on the work of Magrin and that of Daoust and Selby, one can identify several plausible reasons.

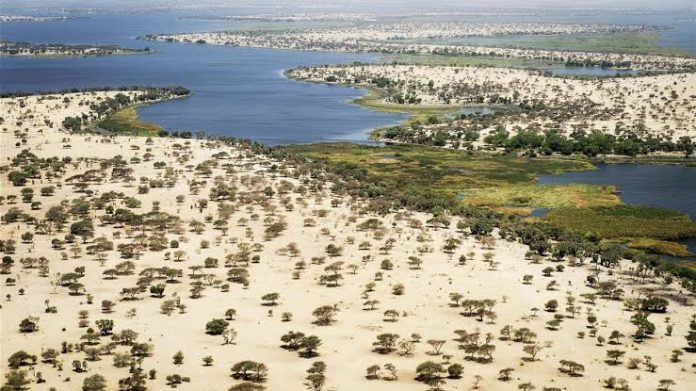

First, there is something peculiar about Lake Chad, something powerfully visual. Right in the middle of the Sahel sits a gigantic lake – a striking sight indeed: it is difficult to look at a satellite picture without thinking the lake is the anomaly, and that it will eventually be eaten up at some point by the surrounding desert.

Selby and Daoust suggest that the narrative in the context of Lake Chad fits with a colonial trope that construes Africa as a continent in perpetual crisis, unfit to handle its environment, doomed to desertification and redeemable only by external intervention.

In the global institutions involved, there is also at play a strong preference for universalising narratives. James Scott had noted that seeing like a state tends to result in globalising, context-poor readings. This is probably even truer in contexts where multinational machines like the World Bank or the Lake Chad Basin Commission are involved. Globalised governance tends to favour “transferrable” narratives that can be carried easily from one terrain to another. The climate crisis is one such example, although its mechanisms and manifestations are always context-specific and may vary significantly from one place to the next. Because the climate crisis has often been summed up as “global warming”, it conveys ideas of heat and drought. This may indeed be the direction for Western Europe, but for the Lake Chad region, it will be affected in partly different ways, some of which may well be equally catastrophic.

Another factor is that states and international institutions are keen on ways to cooperate without creating too much tension. The climate crisis is a non-controversial narrative that depoliticises the Boko Haram conflict and does not attribute direct responsibility for it: this is much easier than talking – not to mention devising and implementing policy – about governance, human rights or global political economy, especially in a context where the states involved are defensive about their record and often opt to resort to using the sovereignty trump card.

There is a final dimension worth considering: the special appeal of “hardware” for policymakers in the Lake Chad Basin and the world over. There is a visibility, a materiality to “hardware” that makes it interesting. It can be both a powerful and lasting symbol of policy intervention (and thus a plausible way to garner legitimacy) and a wonderful opportunity to raise and to spend a lot of money. This can be attractive for a lot of players involved: for the companies that will build the project (the Italian firm that developed the Transaqua project in the 1980s is now in league with a leading Chinese construction company), and also for the Lake Chad Basin states who will get to spend money they would probably not otherwise attract, money which will trickle down in variety of ways, direct and indirect, legal and illegal, at least to their national elites.

The Moral of the Story

Lake Chad is not drying up, but there is a global climate crisis and its signs are manifest in the Lake Chad Basin. The circulation of global narratives is positive, as it can help create a policy community that is better able to address the challenges of today. Nevertheless, those people, institutions and organisations interested in solving the Boko Haram crisis should resist the urge to frame it as a manifestation of the climate crisis.

Instead, they should give priority to the complexity of interconnected dynamics that stand at the very core of the conflict – e.g. Nigeria’s history of inequality, injustice, violence and identity politics – and aggravating factors – e.g. the appeal of, and assistance from, global jihadi organisations (essentially the Islamic State at present) and the cross-border connections that help supply the jihadi.